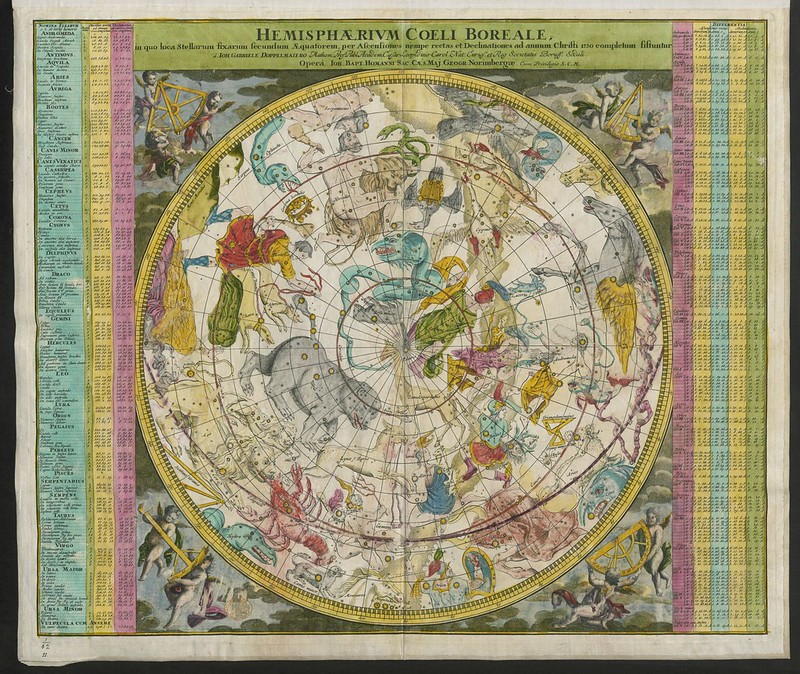

Most of us do not, today, live in desperate need of maps. On the internet we can easily find not only the current maps we need to navigate most any territory on Earth, but also an increasing proportion of all the maps made before as well. You can find the latter in places like the David Rumsey Map Collection, which, as we wrote last year here on Open Culture, now boasts 91,000 historic maps free to download. It will surely add even more, as humanity seems to have only just begun digitizing its own many attempts to make the physical world legible, an art that goes back (as you know if you read the University of Chicago’s The History of Cartography online) to prehistoric Lascaux cave paintings of the night sky.

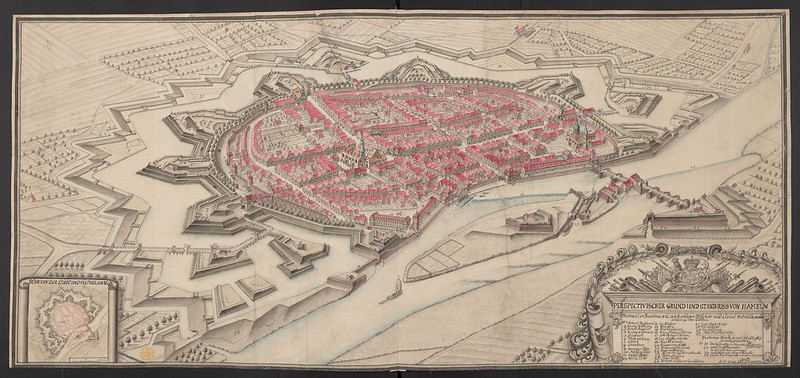

By that standard, the maps currently being digitized and uploaded by the British Library are downright modern — or early modern, to be more specific. Dating between 1500 and 1824, says Medievalists.net, these maps “are part of the Topographical Collection of King George III (K. Top),” which also includes “maps, atlases, architectural drawings, cartoons and watercolors.”

Part of “the larger King’s Library which was presented to the Nation by George IV in 1823,” the collection was amassed “during the formative period of the British Empire” and thus shows “how Britain viewed and interacted with the wider world during this period.”

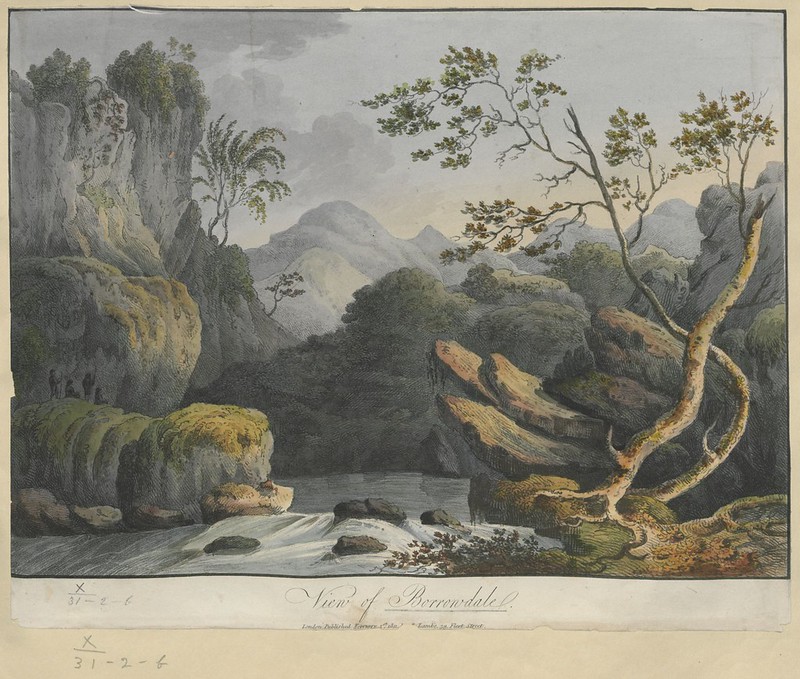

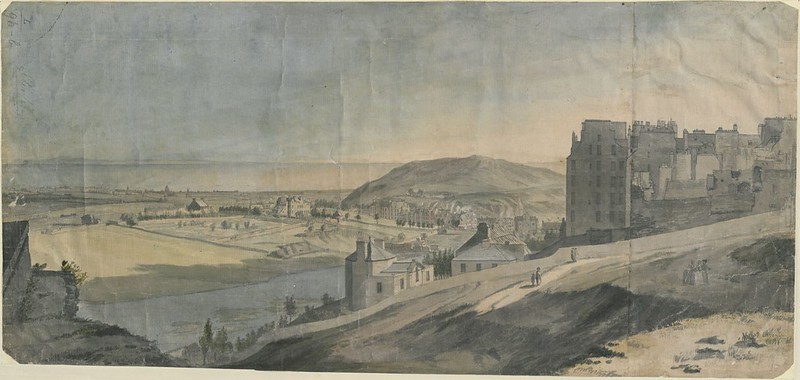

The British Library plans to post 40,000 of these maps (broadly considered), and you can now view the first set of roughly 18,000 at the institution’s Flickr Commons collection. Medievalists.net names as highlights of the full Topographical Collection of King George III such artifacts as “a hand-drawn map of New York City, presented to the future James II in 1664,” “The vast Kangxi Map of China of 1719 made by the Italian Jesuit Matteo Ripa,” “the earliest comprehensive land-use map of London from 1800,” and even “watercolors by noted 18th century artists such as Paul Sandby and Samuel Hieronymus Grimm.”

Many of the pieces the British Library has thus far uploaded to Flickr look like maps to us still today, but just as many, perhaps most, strike us more as works of art. This goes for traditional bird’s-eye-views rendered more vividly (and sometimes imaginatively) than we’re used to, as well for as richly drawn or even painted landscapes, all of which exist to provide a faithful representation of land, sea, and sky. You can view more such images along that spectrum, as well as read their stories in context, at the British Library’s Picturing Places site. The artistic and historical richness exuded by these maps today echoes the more tangible value they had when first created: back then, those who had the maps possessed the world.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario